It is the spring of 1945.

Mussolini is dead and the people of Italy survey wreckage of their country.

For two decades, fascism has been the ruling ideology: individual rights and democratic values were suppressed in favour of the state.

In a village near the town of Reggio Emilia, the people decide to build a school. To raise the money, they sell what the retreating Germans leave behind: an old tank, a couple of vehicles and some horses.

In this school, they will teach the their values: respect, peace, individual expression and collaboration. The antithesis of Mussolini’s authoritarian creed.

A local teacher, Loris Malaguzzi, hears of the project and is inspired. Over the coming decades, he takes a leading role as the school at Villa Cella becomes the first of many. The Reggio Emilia approach is born.

The Reggio Emilia Approach

Back in 2009, I went on a study trip to visit the now world-famous preschools.

The first thing you notice is the quality of the children’s work. It is astonishing.

I’d love to show you some of it but Reggio schools closely guard their intellectual property. We weren’t allowed to take photos, of either the schools or the art. I even asked if they could send me a media pack with authorised images that I could use in this email. They politely declined.

I like to include pictures, to brighten up my stodgy emails, so this made me sad.

But, undeterred, I decided to photograph the books I bought and the notes I took while I was there.

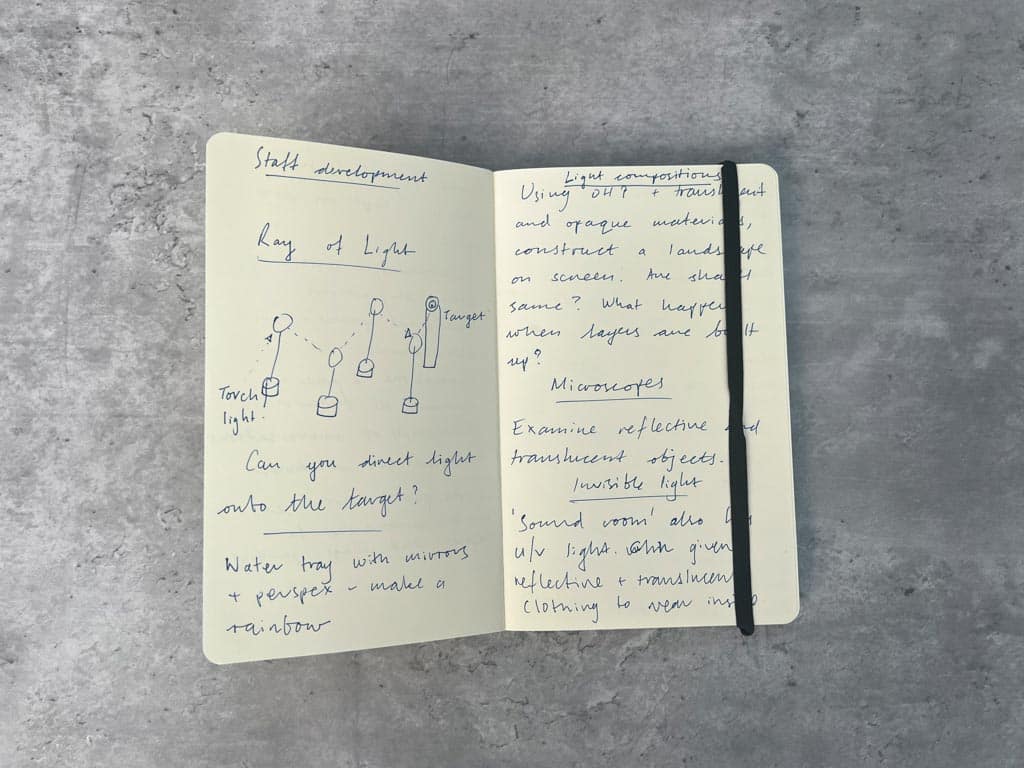

Here is my notebook.

Like a courtroom artist, I had to sketch what I saw. If you zoom in, you’ll see from my notes that I had to document everything in the room because we couldn’t take pictures. In a way, I’m glad because it forced me to really think about what was in front of me.

Here I document a project where the children are studying light. They explore how a beam can be reflected and, through cleverly positioned mirrors, be guided towards a target.

See the Reggio Children website to see what I’m describe in all its glory. In particular, look at the section on the atelier, what we in England would reductively call the ‘art room’. It’s much more than that, of course, as we’ll see below.

Group meetings

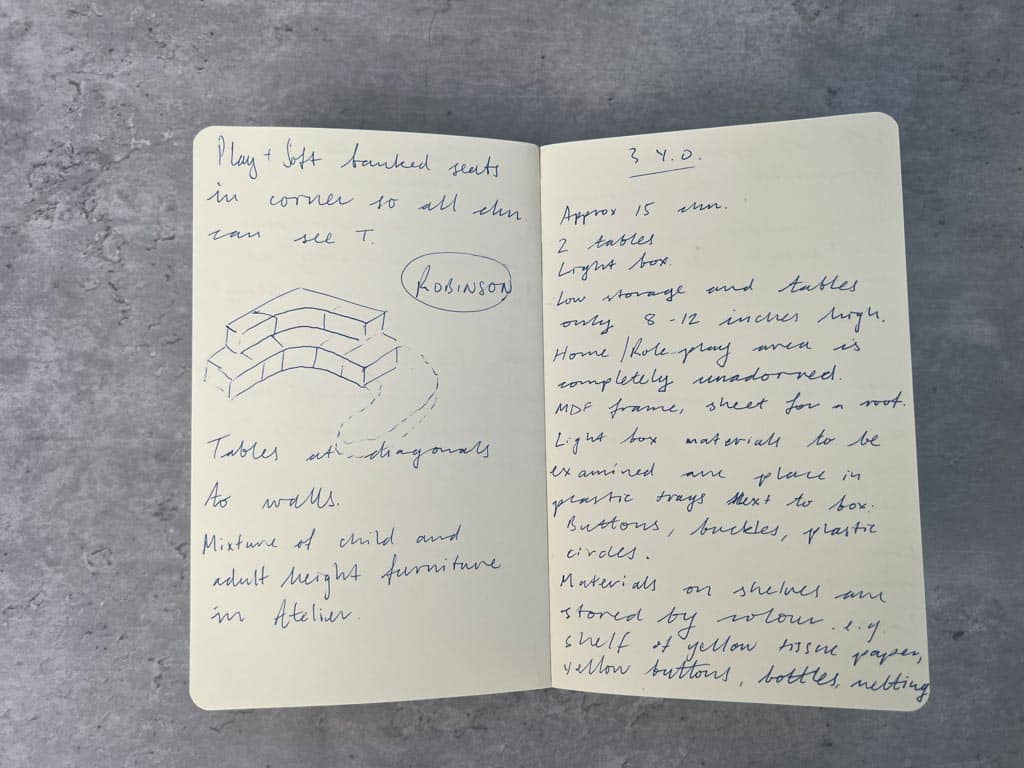

Here’s another one of my sketches. It’s furniture designed for dialogue. In its fullest configuration, it forms a horseshoe shape.

Like the Roman Senate, the preschoolers of Reggio Emilia sit for group meetings on tiered blocks, facing each other like Romans in the Senate, exploring and debating. What will we do today? What materials do we need? What is the status of our project? The plant in the hall is dying. What can be done?

The children take these discussions seriously because they are listened to. Their opinions matter. They believe that they can effect change.

These group meetings are at central to the Reggio Emilia approach but you don’t need a school council to show your child that you value her input. A chat over the breakfast table works just as well.

But really listen. If you are committed to trying this approach, avoid the temptation to pull rank and overrule your child. Not all her ideas will be practical. You can’t follow every whim.

But if she expresses genuine interest in a topic, talk together a while.

Where might it lead?

To see this piece of furniture in action, visit the Play Piu website and click through the thumbnails. Imagine a whole class, listening respectfully to each speaker, and everyone free to contribute.

It’s a powerful idea.

Note: The ‘preschools’ in Reggio are for children aged 3 – 6 years, much older than the 3 – 4 years catered for here in the UK.

“We wanted to recognise the right of each child to be a protagonist and the need to sustain each child’s spontaneous curiosity at a high level.”

Loris Malaguzzi

5 Plus and Reggio

5 Plus is not the Reggio Emilia approach. But I take its philosophy as the jumping off point for our projects.

We’ll take a deep dive into the approach, looking at what makes it so successful and how you can apply its methods at home.

If you’ve spent any time on Pinterest or Instagram looking at children’s activities, you’re sure to have come across invitations to play. These are interesting and hopefully novel set-ups that inspire your child to play. Think tuff spot full of blue jelly and some plastic fish. Or a set of wooden blocks arranged as an incomplete bridge. Can you finish the construction and help the Three Billy Goats cross the river?

It’s great for toddlers and preschoolers, who need a bit of guidance. They are still new to imaginative play and are liable to get bored if the same materials are presented too often. They can’t yet see the possibilities for play. I love blocks, but if you only ever use them to build towers, the fun gets old.

But older children are ready for provocations.

Provocations are intentional, open-ended prompts or setups that stimulate children’s thinking, creativity, and exploration. They evoke curiosity, invite questions, and provide opportunities for deeper learning by drawing upon children’s interests and encouraging diverse ways of expression and discovery.

In other words, they draw out deeper thinking and lead to longer projects. Not just the work of an afternoon but a multi-day or multi-week investigation.

What kind of investigation?

It can be anything. The important thing is that it captures your child’s interest. And it is not something that you have imposed. Your child, like the children in the group meeting, collaborates in its creation.

The future is a lovely day

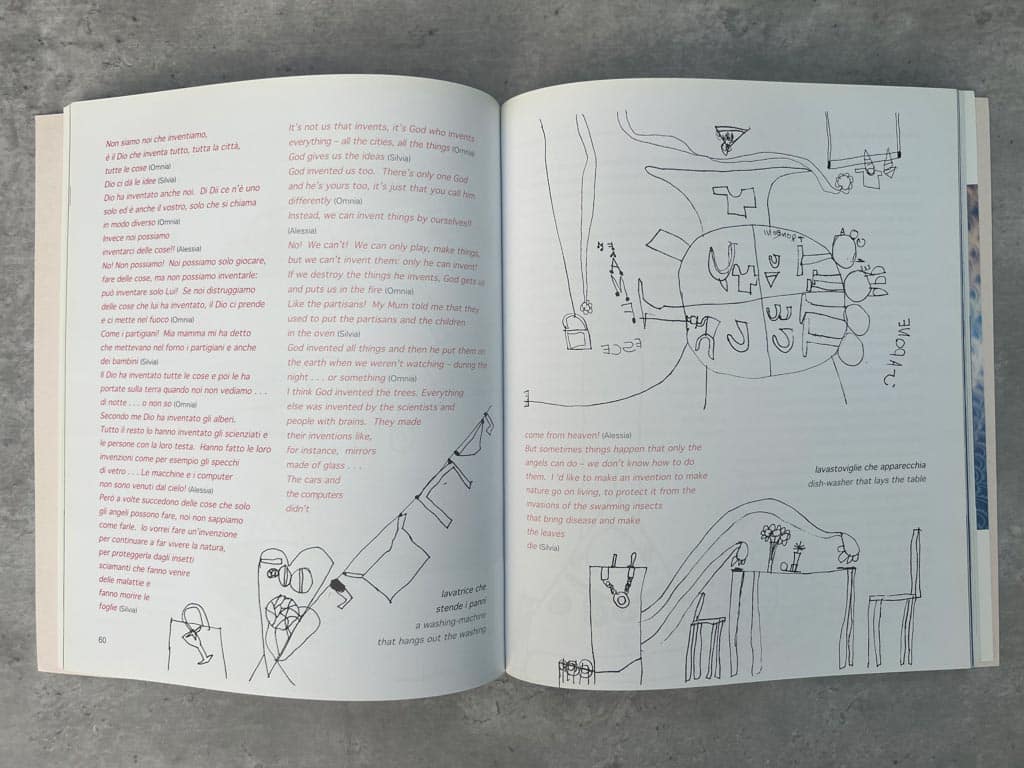

This wonderful book describes a project of the children at the Sant’Ilaria d’Enza preschool.

What will the future look like?

A washing machine that hangs out the washing.

A dishwasher that lays the table.

Can you picture the children sitting in their group meeting, discussing possible futures and ways to represent those ideas in their work?

Now picture them decamping to the atelier to plan and to make. Imagine the excitement. It’s not just a quick scribble of a household appliance.

What will we need? We’ll have to look inside our dishwasher and see what it’s like. What other machines could we examine? Engineers are laying new cables in our road. We could watch the digger at work and see how it moves. Perhaps there’s something at the design museum that could help us?

Some children will choose clay, others junk materials.

What would your child do? How does she like to represent ideas? Lego Technics? Meccano? Poetry?

Poetry?

Yes, a topic I’ll return to in a future email is the idea of the Hundred Languages of Children. It’s central to the Reggio approach. Children have ‘100’ ways to express their thoughts: dance, music, clay and paint.

Loris Malaguzzi explained it in a poem. Read it here.

The atelier is a place to express the 100 Languages, it’s not just an art room.

When educators in the rest of the world first discover Reggio, this is the mistake they sometimes make. They see the beautiful pictures and believe that a Reggio classroom is all about art.

But it’s not, it’s about thinking. It’s about finding your voice and being heard.

Final word

We look at the Reggio approach in great detail in 5 Plus, our new course for children aged 5 – 10. But if subscribing isn’t right for you, you can expect some more glimpses of the approach in upcoming newsletters.

The Reggio Emilia Approach, originating from the city of Reggio Emilia in Italy, is a distinctive educational philosophy focusing on preschool and primary education. This approach upholds the belief that children are powerful, resourceful, and competent beings with the desire and ability to construct their own learning experiences.

Key Features of the Reggio Emilia Approach

The Child as an Active Participant: At the heart of the Reggio Emilia Approach is the belief that children are capable of constructing their own learning. They are viewed as protagonists, collaborators, and communicators with an instinctive curiosity.

The Role of the Educator: Teachers are not merely transmitters of knowledge but are partners, nurturers, and guides who stimulate thinking and foster exploration.

The Importance of Collaboration and Communication: Communication is a process, a way of discovering things, and is viewed as being essential to the child’s cognitive development. The approach encourages collaboration between children, teachers, and parents.

The Concept of the ‘100 Languages of Children’

The ‘100 Languages of Children’ is a core concept of the Reggio Emilia Approach. It refers to the idea that children have hundred ways of thinking, expressing, discovering, and learning. Children are encouraged to express themselves however they wish, whether through words, movement, drawing, painting, building, sculpture, shadow play, collage, dramatic play, music, and so on. This concept celebrates the multitude of ways children can express their thoughts, ideas, and understandings.

Understanding ‘Provocations’ in the Reggio Emilia Approach

A provocation in the Reggio Emilia context is a stimulus that teachers use to ignite children’s interest and to stimulate thinking. Provocations are resources or experiences that provoke thoughts, discussions, questions, interests, creativity, and ideas. They are often open-ended, inviting children to explore and interact in ways that are meaningful to them. Examples might include natural materials like pinecones and leaves, art supplies, or a photo of a rainforest.

‘The Environment as the Third Teacher’

The Reggio Emilia Approach sees the environment as a crucial contributor to education – often referred to as ‘the third teacher’. The organization and aesthetic of the learning environment is thoughtfully arranged to provoke wonder, curiosity, and engagement. Classrooms often feature natural light, indoor plants, and real-life materials to foster a connection with nature. Every material in the space is considered for its purpose and potential to support engagement.

Implementing Reggio Emilia Principles at Home

Parents can bring Reggio Emilia principles into the home, too. This could involve setting up a ‘provocation’ on a table for your child to explore, or taking the time to truly listen and converse with your child about their thoughts and ideas. It might involve using natural materials and objects for play and exploration, or even redesigning a playroom or bedroom to inspire creativity and discovery.

Reggio Emilia Approach FAQs

Q: Is the Reggio Emilia Approach suitable for all children?

A: Yes, the approach is designed to respect the individuality of all children. It allows children to explore and learn at their own pace and in their own way, making it adaptable to a wide range of learning styles and abilities.

Q: How do teachers assess children’s progress in the Reggio Emilia Approach?

A: Rather than traditional standardized testing, educators assess children’s progress by documenting their work and interactions. Teachers maintain detailed records including photographs, transcripts of children’s thoughts and explanations, visual representations of their thinking, and replicas of their creations.

Q: How can I implement the Reggio Emilia Approach if my child is already in a traditional school?

A: You can incorporate the principles of the Reggio Emilia Approach at home by providing an enriching environment that encourages exploration and creativity. Also, consider how you interact with your child: listen to their ideas, encourage their questions, and foster dialogue and cooperation.

Q: Does the Reggio Emilia Approach require specific materials or resources?

A: No, the approach values the use of natural, everyday materials, emphasizing the exploration and manipulation of such materials to learn about the world. It’s not about buying expensive or specific educational resources but about using what is available in creative and meaningful ways.

Final word

The Reggio Emilia Approach’s focus on child-centered exploration, communication, and respect for the child’s capabilities offers children a dynamic and engaging environment for early learning. By adopting its principles, parents can nurture their child’s curiosity, creativity, and love of learning, setting a strong foundation for their future educational journey.