Dr Helen Jones looks at what art means to children and how to provide quality opportunities for drawing and painting at home

Table of contents:

- Introduction

- Why paint? The benefits of making art

- How do the stages of visual representation develop?

- How to support your child with art

- Final word

‘Intelligence itself is built upon that which we crudely term ‘children’s art’’.

John Matthews, Drawing and Painting: children and visual representation.

Introduction

As an artist and a teacher of art you might think I have a lot to teach you about children’s art. But I haven’t. In fact, it’s our children who can educate us.

Having observed children of all ages over the past 11 years, I’ve been fortunate to gain some fascinating insights, simply by letting them show me how they make sense of the world through art. I’ve watched in wonder as their drawing develops, how it links to higher level thinking, and how they are communicating visually.

So often when it comes to our children’s art, it’s tempting to think that they are just messing around with pens and pencils. Art making in infancy can be hugely underrated and in mainstream school curricula it can even be suppressed. Yet science is showing us the huge, invaluable cognitive benefits of art. Scientific trials have revealed young children quickly abandon ‘dummy pens’ without ink, uncovering their strong desire to make marks… but what good does it bring?

Why paint? The benefits for children of making art

Language foundation:

Drawing is an integral part of the way children learn signs, symbols and representation. According to professor of art John Matthews, in his book Drawing and Painting: Children and visual representation, drawing forms ‘the basis for all thinking… what adults call children’s art has a central role to play in cognitive development.’ Art is a visual language – a universal one, and a key to unlock the door of communication.

Cross-curricular learning:

Children learn about gravity, physics, perspective, maths, anatomy, and myriad other concepts all through drawing. I explore art’s symbiotic relationships in my article on what children’s art can teach us. But while art can enrich learning in other areas, it can also be used for so much more.

Joy:

When creating art for art’s sake – in a self-motivated mode of personal expression and glee – we can be absorbed in our own inventive worlds. The Spanish painter Joan Miro once said ‘A simple line, painted with a brush can lead to freedom and happiness’. It certainly does for me!

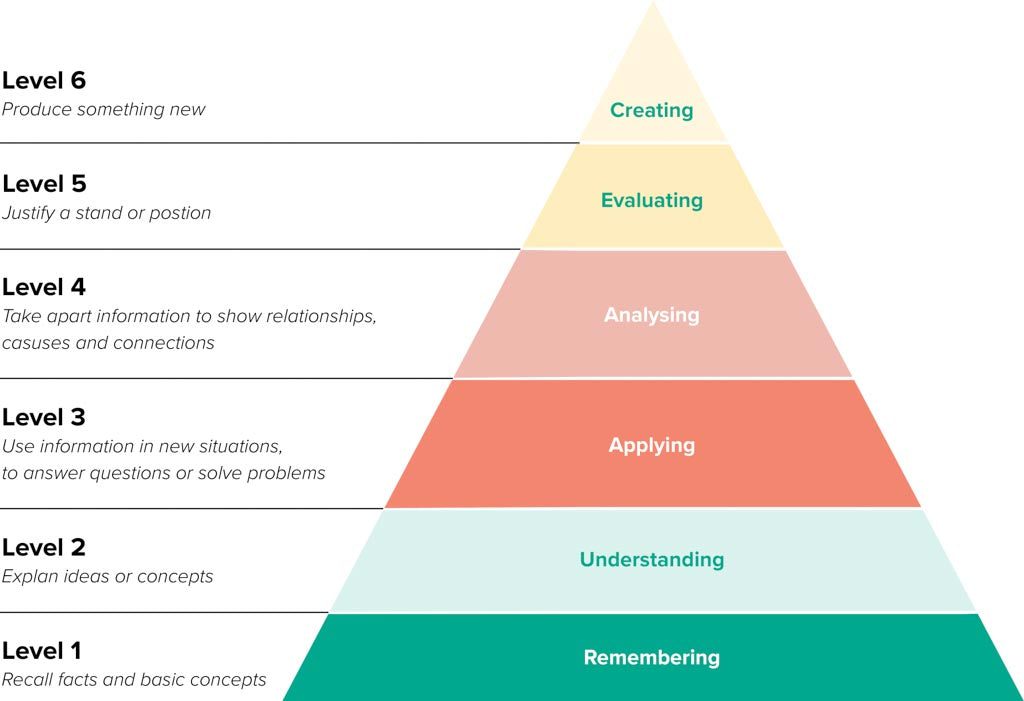

Higher level thinking skills.

Have you ever come across Bloom’s taxonomy? It’s a hierarchy of cognitive skills, displayed in the form of a pyramid, with ‘creating’ at the top. Looking at the illustration below, can you see how drawing and painting might sit at the higher end? They involve ‘rapid and complex decision-making’ (Matthews) all while figuring out how to show information about what is – or isn’t – in one’s world and our relationship with it.

Observation:

Drawing trains us in the indispensable, lifelong art of observation. Lots of people tend to think we draw to represent reality but in fact a lot of the time what I see from children is the reverse: they draw and then they start noticing similar shapes in reality. Being able to observe and gather information about the world is a life skill.

Emotional regulation and self-expression:

Art can create a mood, record our thoughts, express a feeling or intensify a preexisting one. Art is the ‘go to’ when we want to say something which cannot be said.

Fine motor skills:

Precision and finger dexterity involved when controlling a paintbrush, crayon, pen or pencil are vital, transferable skills, that aid your child with handwriting, tying shoelaces and all those other necessary, but oh-so-fiddly jobs.

Cause and effect:

As soon as you move the paintbrush or pen, a mark is left. This instant feedback, unique to drawing and painting, makes us aware of our body and the consequences of our movement. Children learn the crucial lesson that their actions have an effect on the world. They can make a difference to it. Matthews says: ‘The most dramatic way the child realises this is when she draws. It is only through drawing that the infant receives a record of her movements.’

Ok, so you’re sold, it’s good right? But how does it begin? What should we look out for?

How drawing and painting develops

It’s easy to assume that children’s mark making is a haphazard collection of uncontrolled scribbles. This is far from the case, says Matthews:

‘Children’s drawing has organisation and meaning all the way from the beginning, when many people consider infants to be scribbling.’

While these apparently ill-controlled movements can appear mindless, they are far from it – they mask lots of thought and sensitivity to the drawing surface. As child psychologist Norman Freeman explains in Strategies of Representation in Young Children: ‘ a continuous contact line teaches coordination, control, cause and effect, and what’s more, the child’s aim is, surprisingly, rather accurate.’

There are some recognisable drawing traits that emerge over time in infants.

Vertical arc, horizontal arc and push – pull.

These are the three basic mark-making movements, which enable further marks and shapes to emerge. These are the foundation of children’s mark making. Horizontal arc; an arcing shape with a horizontal swing of the arm, pushing and pulling movements, and vertical arcs; a swing upright against the page.

Closed shape.

This can close off areas and represent the notion of inside or outside. It can also represent front-on views of objects and, more commonly, faces. The introduction of the closed shape marks a developmental milestone in thinking and increased motor control.

Layering.

Placing one object over another deals with concepts of ‘in front’, behind or hide and seek. Connectivity, going over, going under, going in, going out or going through. These are vital concerns that can often only be rectified through visual play.

Landmarks.

This is when children start to consider the format and layout of their drawing, such as the position of an object, and parts of the body becoming coordinated. A mark becomes a landmark, which all other marks are formed around and in relation to.

Parallel lines.

Through exploring side-by-side lines, kids can grasp the concept of parallelism way before they are even introduced to the term parallel. What a head start!

Right angular connections.

I have seen how fascinated children can be by the beginnings and ends of lines and this often precedes their realisation they can add a new line onto the preexisting one, at a right angle. This forms the basis of many recognisable shapes.

Travelling zigzags.

I often see children create meandering zig zag lines when listening to music – perhaps it is the repetition? Or our endless fascination as a human species with pattern, which we are predisposed to detect.

Continuous rotation.

This often deals with issues of process, movement and repetition. Each encircling of a previous circle adds a new layering of understanding and a subtly different perception.

However, this should all come with a cautious caveat: there is no tick-box approach. I don’t wish to create a stage like illusion, where children go from one form of mark making to another, incrementally, climbing the art ladder: it’s not that simple.

Many children swing between these different types of marks. Some of these actions may then come together to form stick men, and fully developed pictures.

When children change the subject matter they adapt the way they use the shapes and lines to give them different meanings. But there are times when children might seem frustrated because they cannot find a way to represent their new understanding about the world.

In times like these adult encouragement and support is especially vital, if not throughout the entire creative process.

How to support your child

Some might think there’s not much use in supporting your child with drawing – they either have ‘it’ or they don’t, right?

Wrong!

While it is true that there is a certain amount of genetic disposition, in my experience the majority of artistic talent is derived from the support a child receives and the amount of hours and effort they invest.

Pablo Picasso once said: ‘all children are born artists, the problem is how to remain an artist.’

The answer to the problem could lie in nurture.

Matthews says: ‘much of children’s drawing and painting is self-initiated. The contribution made by adults is crucial.’ Children need opportunities and the encouragement to create, and if this is not given, the bright star of creativity can dim.

Children can develop their visual storytelling skills with the right support.

Resources and opportunities.

Providing basic art materials, (non-toxic paints and paper, pads, pencils) and setting these up (whether on an easel, table or messy mat), puts creative experiences in children’s paths. It gives them the option.

Show an interest.

Both in your child’s creative productions and art in general. Children are more likely to engage if they see you enjoying or partaking in art, however it is far more important to be encouraging, supportive and nurturing of creative opportunities, then to be artistic oneself.

Encourage.

I have come to understand that praise is far more potent when used specifically. Rather than saying a drawing is lovely, consider what is lovely about the drawing. And is it really ‘lovely’ or is it ‘exciting’ or ‘expressive’ and what is promising about how they have approached the whole process, as well as the outcome?

See without prejudice.

Ibid argues that the problem for adults is not one of simply learning what to say, but of learning to see – and of seeing with impartiality. So when your child wanders up to you with glee at what they have produced, try not to respond with criticism. As despite first appearances, our child’s art is not full of errors. It’s an interaction of what is unfolding within them and what’s in their mind’s eye. Try to understand it, show curiosity and pleasure, while helping them to articulate it. As Matthews suggests: ‘Look for meaning behind all their actions.’

Don’t meddle.

Interfering and dominating your child’s productions can stunt confidence, independence and creativity. Matthews writes: ‘It is grossly insensitive to manipulate and interfere with children’s work, sticking things on it, cutting it up, repainting it and generally communicating to the child that her efforts are inadequate. I got a recent communication from my daughters’ childcare explaining their shift to child led art, without the adults adding finishing touches or attempting to control the process. They advised: ‘while it might not always be ‘picture perfect’ it is as unique as the child who has made it.’ I cherish those pieces so much more knowing that.

Display.

Ever wondered why putting up kids drawings on the fridge, cupboard doors and walls is such an institution? It says, ‘you are appreciated, included and celebrated’. It helps kids to see they are building up a collection and allows them to bear witness to their own progress.

Do nothing.

‘Sometimes, simple permission is all that is needed to promote creative thought. Sometimes, the best thing [we] can do is nothing’ says Ibid. Allow this creative process to happen and try not to interrupt unnecessarily (as if what they are doing doesn’t matter). But how do kids get better if we don’t support them directly? Don’t worry, says Matthews: ‘They do much of the work themselves, as they try to resolve ambiguities in their drawings which they find unsatisfactory.’ Phew! We can take our teacher hats off and become an intellectual companion who appreciates their art instead.

Final word

I hope in reading this you have discovered how beneficial art making can be for children and the multitude of advantages it brings. However as much as endorsing art making is a good thing, it should be engaged in for its own sake; children creating artwork for themselves, to serve their own developmental needs and intentions.

The main takeaway really though is how crucial support, encouragement and the right environment can be to developing artistic talent. As Matthews writes: ‘By supporting children’s paintings and drawing we are empowering them. We are giving them some way of controlling their lives.’

So what are you waiting for? Go, create!