Do you ever wonder what your child’s drawings are about?

Do you look at them and think they’re a bit messy? Do you wish she would draw something figurative?

Happily, understanding children’s drawings is easy. All you need is a basic grasp of graphic schemas.

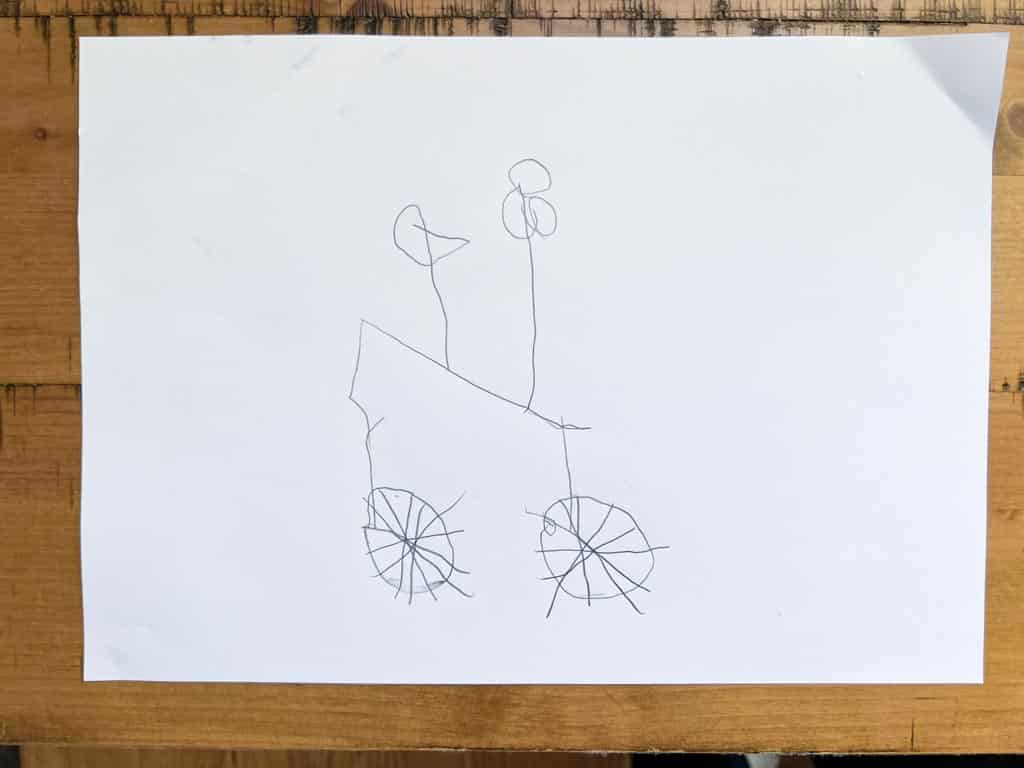

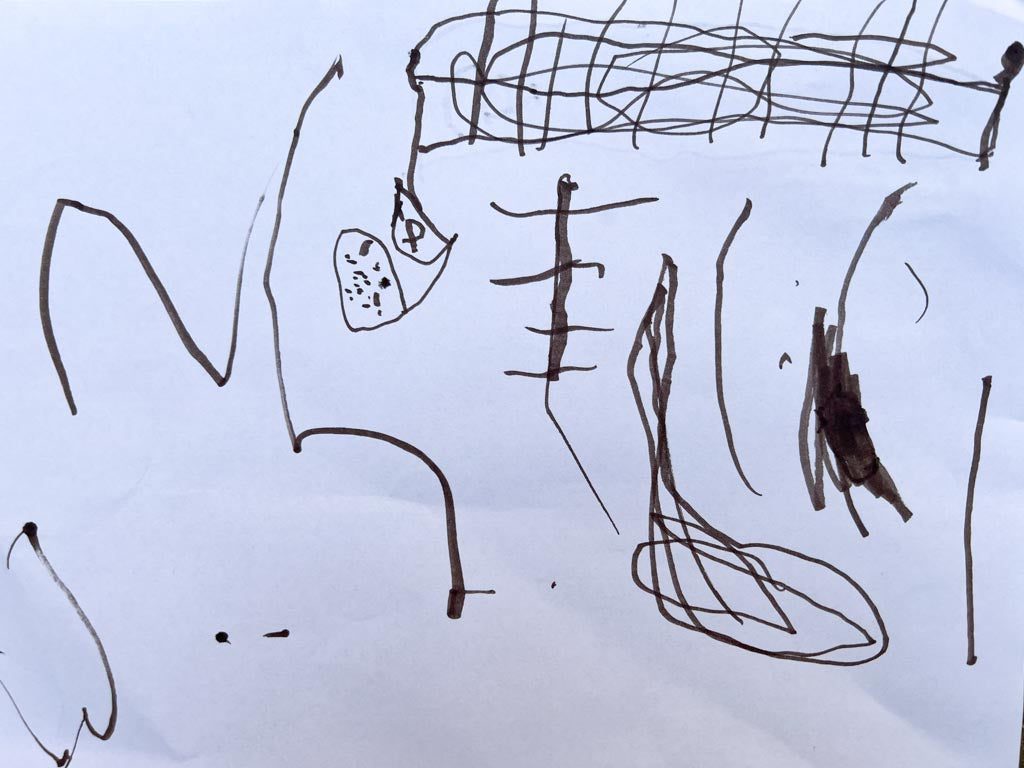

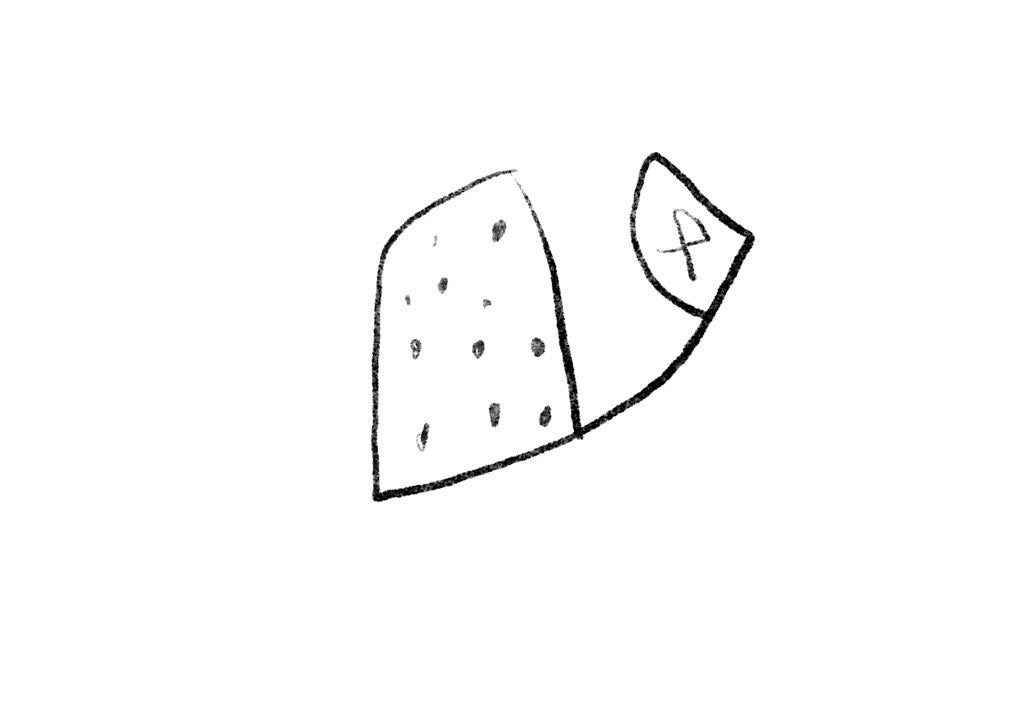

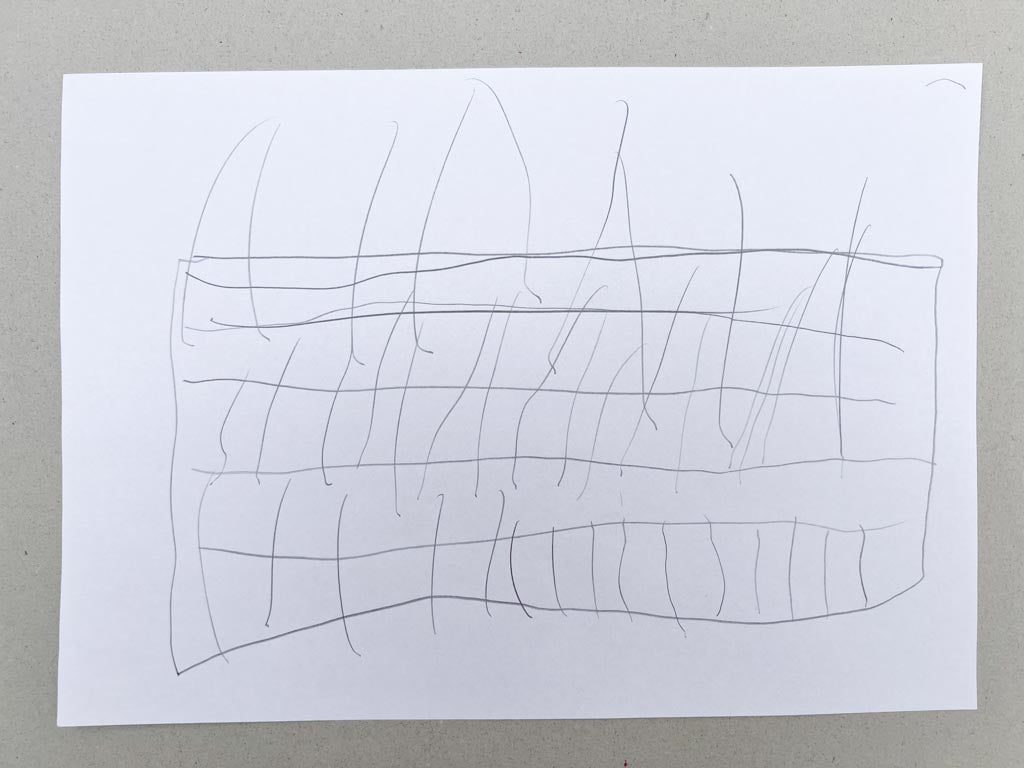

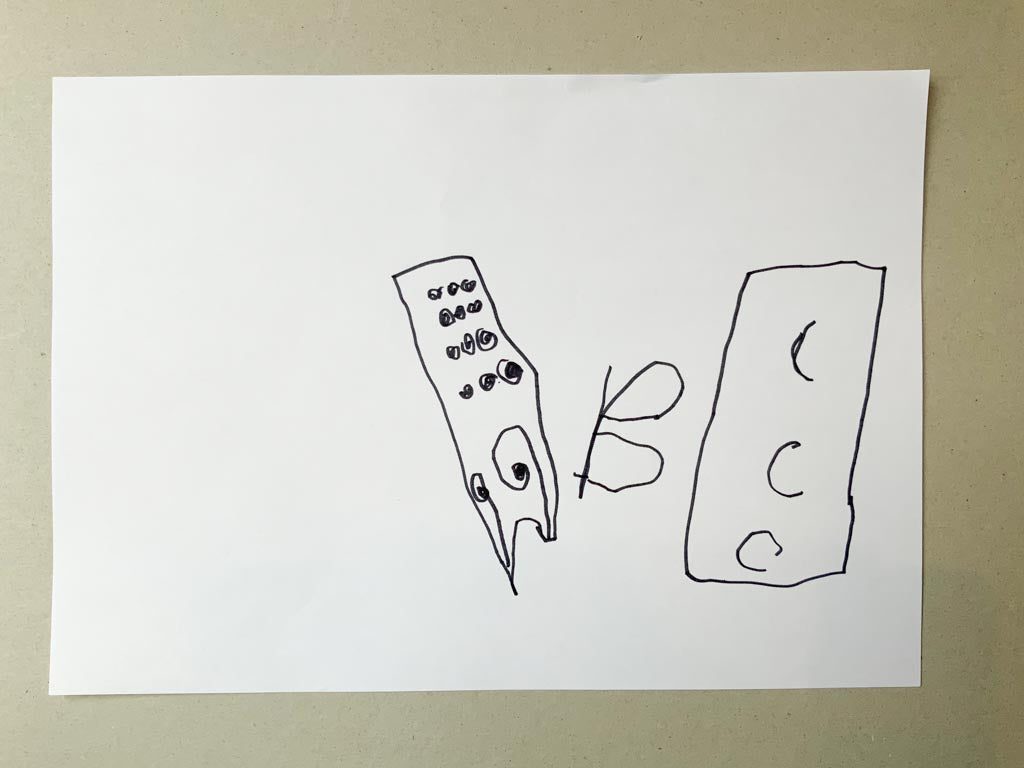

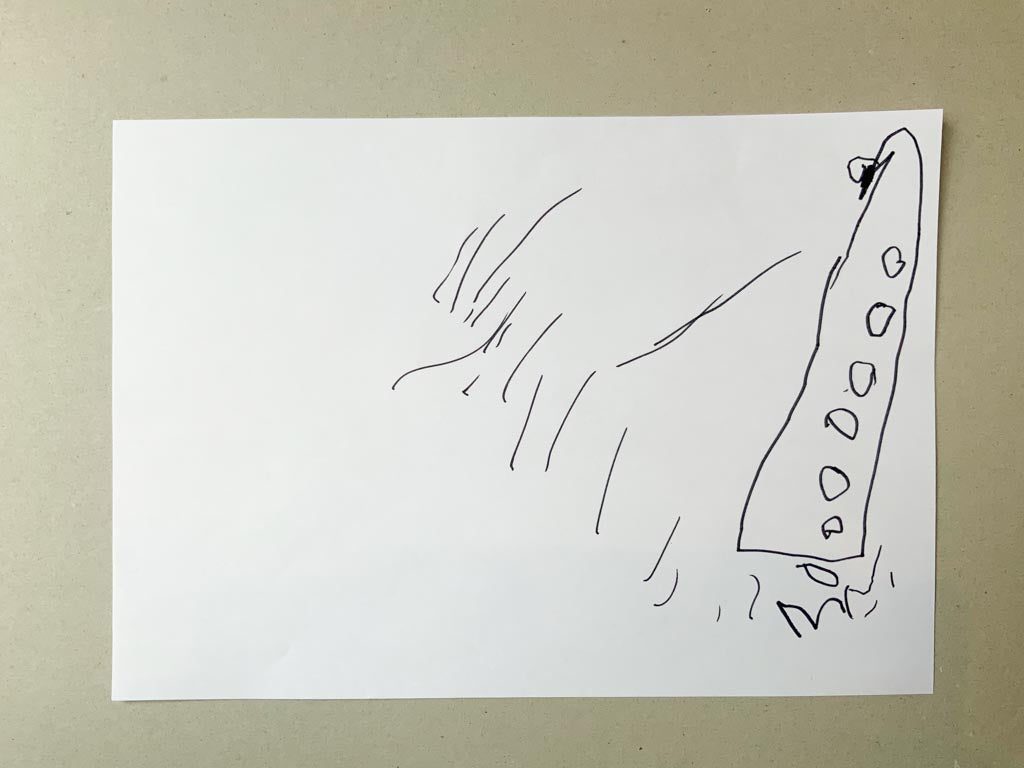

My youngest is now four. Here is something she produced this week:

Figure 1

Hmm… Picasso? Miró?

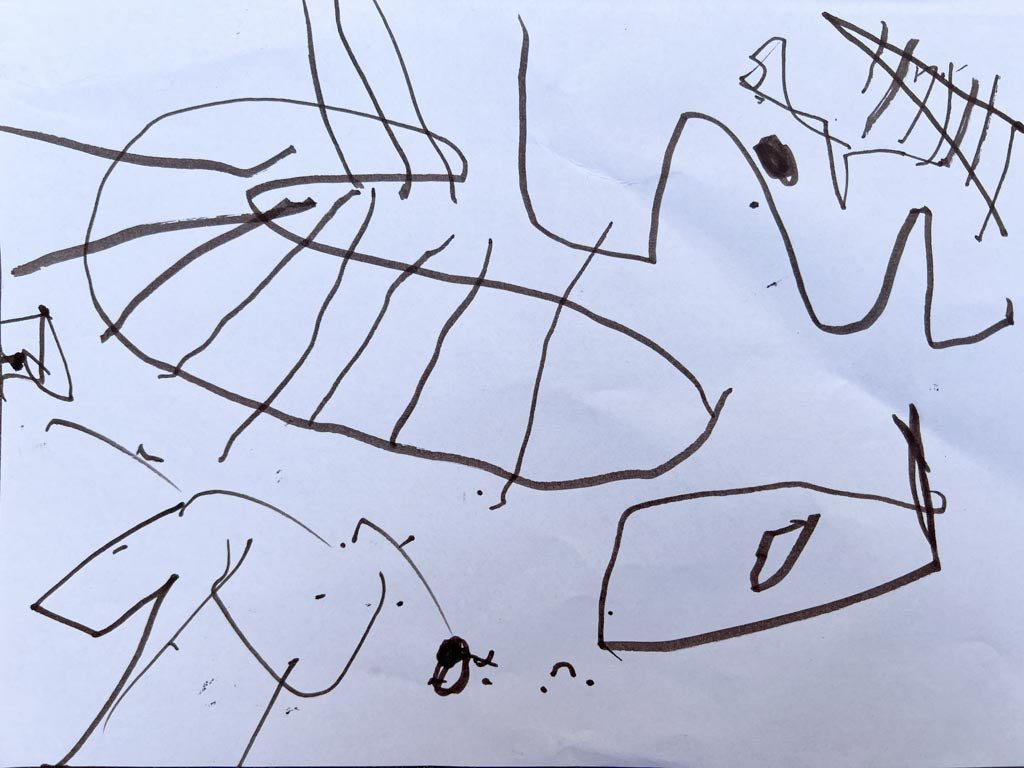

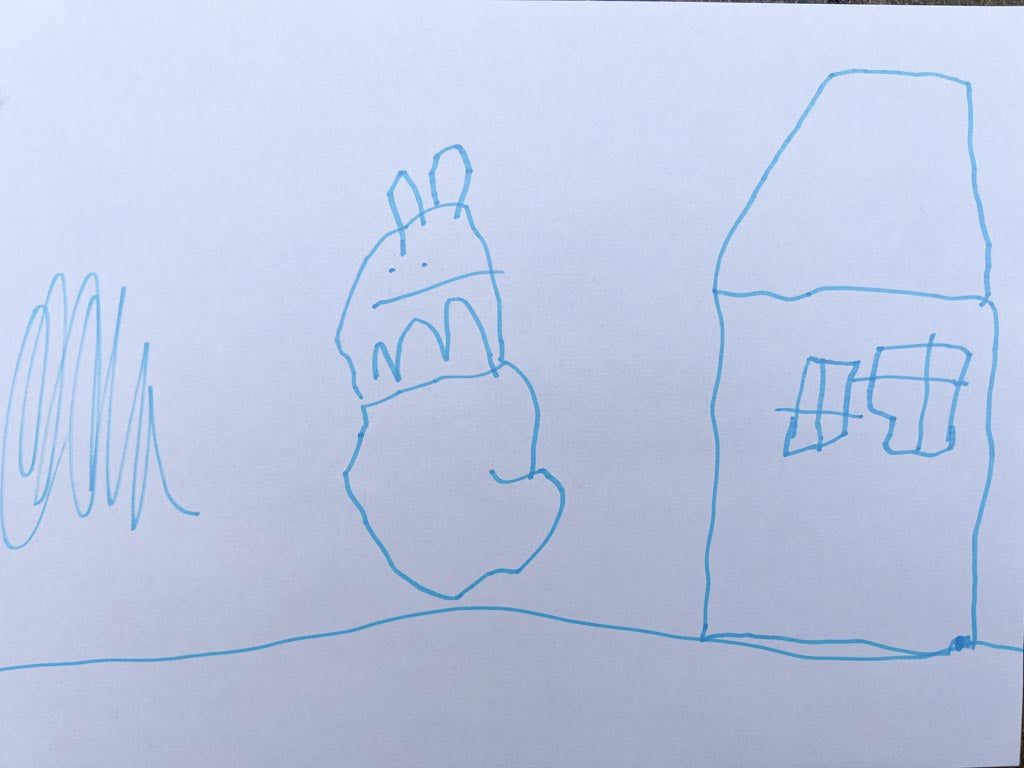

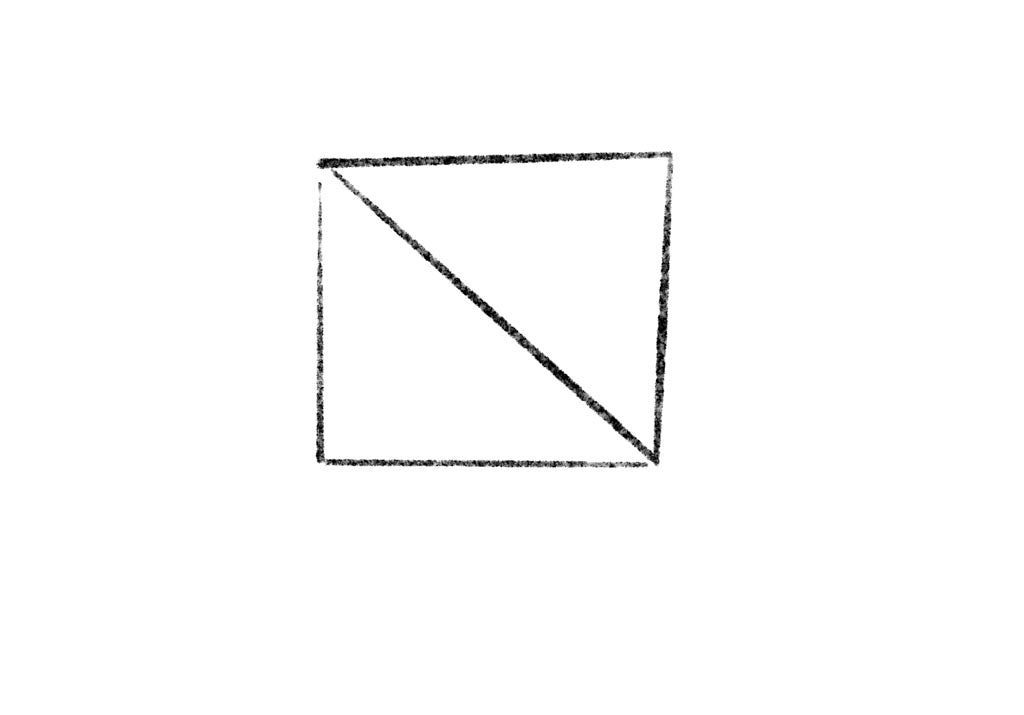

Here’s another picture of hers, drawn on the same day, of the Big Bad Wolf outside Grandma’s cottage.

Figure 2

So she can draw! I don’t know about you, but I was starting to get worried.

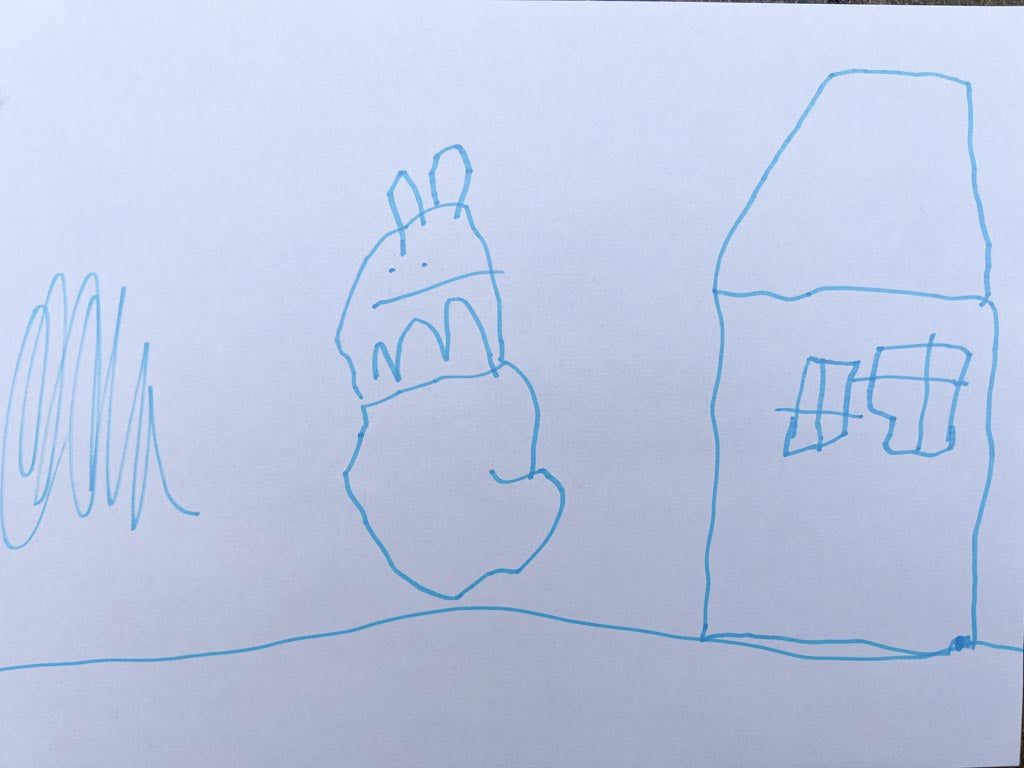

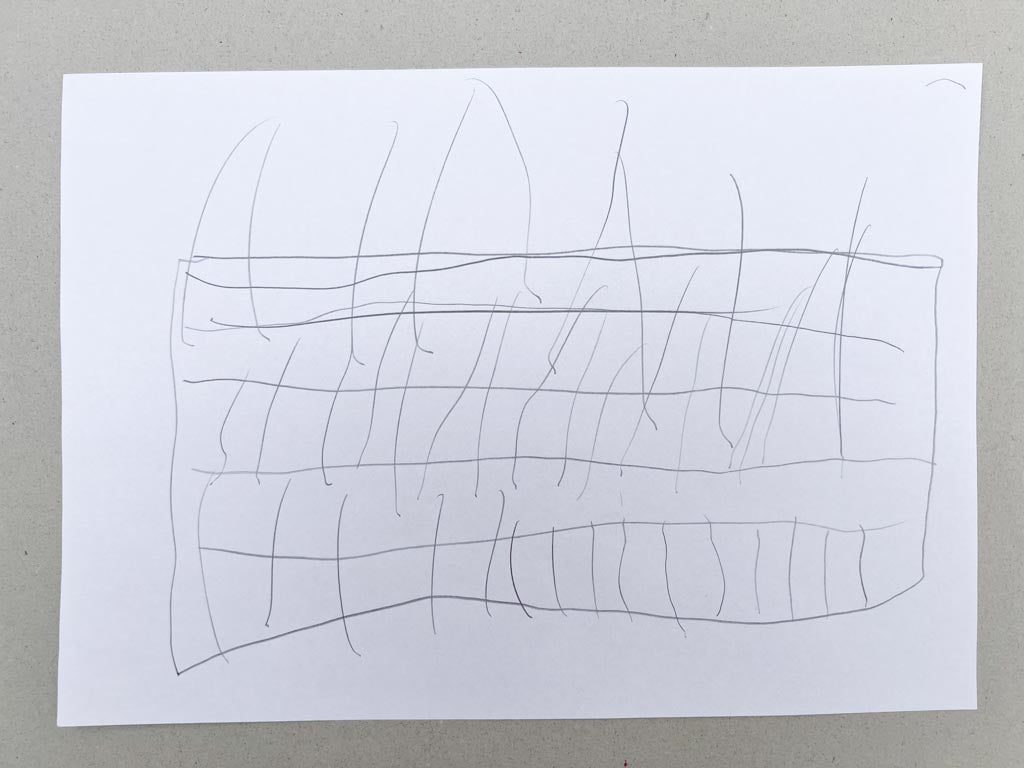

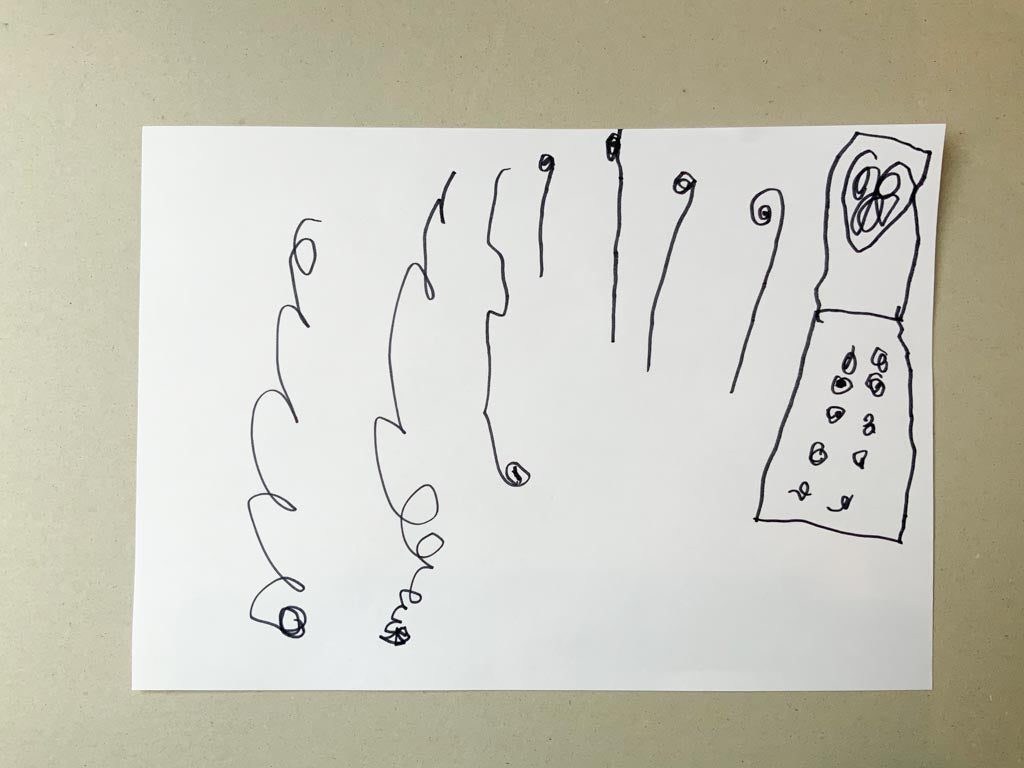

But a day later, we were back to this…

Figure 3

What’s going on here? Why would a child who can clearly draw when she puts her mind to it, spend hours on seemingly meaningless scribbles?

The answer is that these scribbles have meaning after all.

If you’ve spent any time on the 100 Toys site, you’ve probably come across my article on schemas. As I explain in the post, schemas are mental models of things we have encountered in the real world.

Schemas are a kind of shortcut. They save us having to think about how to do something from scratch every time. They are a repeatable pattern we can rely on to complete a task.

If I decide to throw a ball, I know that it will go in the direction my arm moves. Over time I learn that it will arc up into the air and then come down. I learn that it will bounce and continue along in the same direction.

I don’t have to wonder which way it will travel. Through repeated experimentation, I already know.

My schema saves me from going back to first principles every time I encounter a challenge.

There are schemas for rotation, positioning, enveloping, orientation, and all kinds of other movements. We sometimes call them action schemas.

Schemas for drawing

But as well as understanding how things move, our children have to form mental models of how things look. They need schemas for form as well as function.

Toddlers explore ideas through movement, but by the time your child is a preschooler, she is starting to manipulate things in her mind. A toddler lines up blocks or builds towers in order to explore the idea of connecting; a preschooler thinks about how she can place those same blocks to represent a crocodile’s teeth or make an enclosure for her toy animals.

So, back to my daughter’s drawing.

Look again at the marks she made. Can you see any common patterns?

She is exploring how lines intersect. She could do this as easily with blocks or matchsticks but today she is using a pen.

She is developing graphic schemas. These help her make lines and curves and position elements on the page. At the moment my daughter is particularly interested in grids, enclosures and enveloping.

A year ago she was interested in horizontal and vertical lines but now she is learning to co-ordinate the two to make grids. Once you can organise lines in this way, the world of letter formation opens up for you. The following letters all just combinations of these two lines:

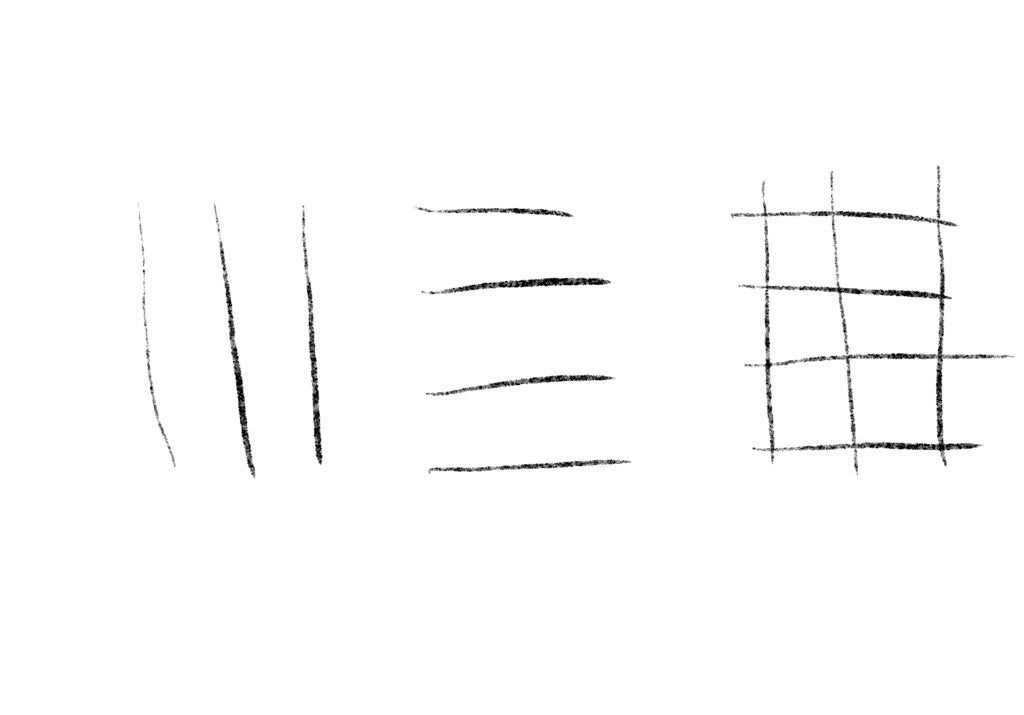

Diagonals are hard

Just because your child can draw a grid, it doesn’t mean she is ready to form the other letters.

Take another look at the Big Bad Wolf:

If I’d asked my six-year-old to draw him, she would have given him pointed ears and jagged teeth. And the house would have had a pitched roof. But it’s not so easy for my youngest.

Me: I like those ears. Tell me why you chose to draw them like that.

Daughter: Because I can’t draw triangles.

I’d already suspected as much but it was interesting that she knew that about herself.

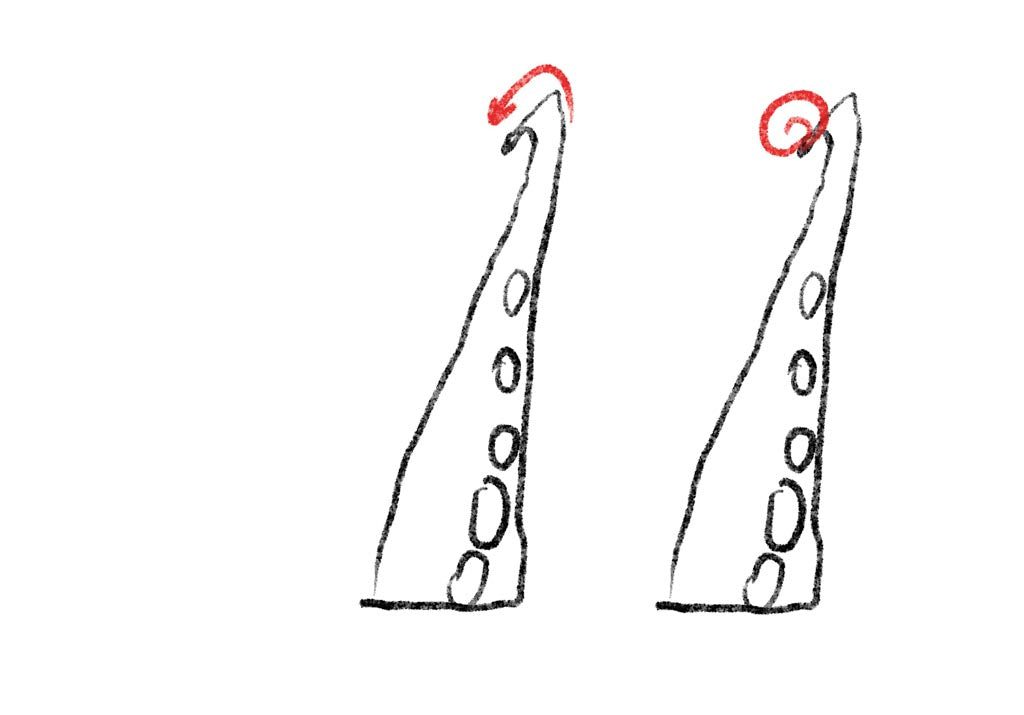

It’s not easy to draw a triangle. Once you can draw a grid, squares are straightforward, but three-sided shapes are much harder. It’s hard to go up to a point and then come back down at exactly the same angle and using a line of exactly the same length. Early attempts look like squares with sloping sides:

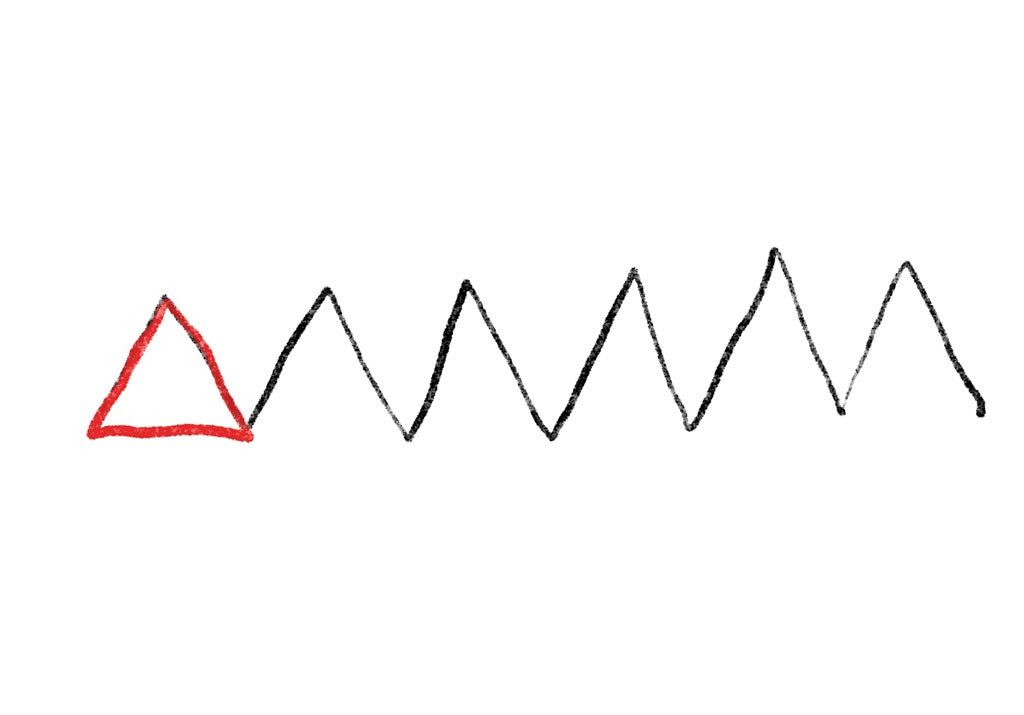

First you have to practise zig-zags, which are really just ‘open continuous triangles’:

As we saw above, horizontals and verticals lead to letter formation. Mastering the diagonal line leads to triangles, zig-zags and the letters Z, X, V, M, N, Y, W and K.

EDIT: Just before publishing this article, my daughter drew another picture. We had been practising zig-zags (you can see them showing faintly through from the other side of the paper) and they reminded her of something: The Big Bad Wolf’s ears. The triangular ones she’d been trying to recreate. No more rounded bunny ears for Mr. B. B. Wolf!

She has modified her schema for drawing triangles, and over the coming days I now expect her to produce a variety of pictures featuring zig-zags and triangles: Dragons’ teeth, dinosaurs’ spikes, stairs and houses with pitched roofs.

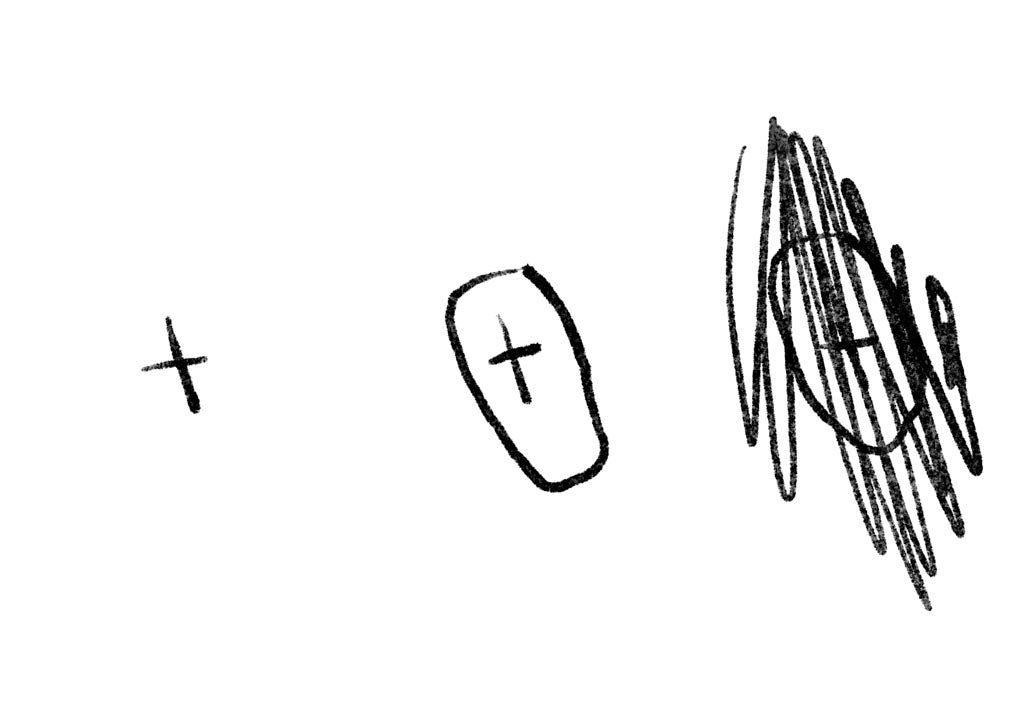

Enclosing

In Figure 3, there’s a shape containing some dots, and a second one containing a cross. You can see a close-up below.

Me: What are you drawing there?

Daughter: They’re inside. I put them in.

Who, or what, ‘they’ are isn’t clear. I don’t think it matters to my daughter. All she cares about is the opportunity to enclose something.

Enclosing is yet another action schema which, as you can see, can also be represented graphically. We can enclose toy animals with a fence, join hands to enclose a friend within a ring or draw a circle around marks on a page. The idea is the same.

Enclosing is also useful when writing. All these letters contain closed off space of some kind: a, b, d, e, g, o, p, q, A, B, D, O, P, Q.

Again, it’s clear that drawing leads directly to letter formation. And before drawing, your child made enclosures with blocks and ran round in circles. Not a worksheet in sight!

Enveloping

One of the first big concepts a baby develops is object permanence – the idea that something hidden from sight continues to exist. This is why babies love peekaboo and hiding objects under cups.

Toddlers take this idea and turn it into the ‘posting’ game. They like to explore how things disappear when posted into holes. Sometimes these objects reappear by dropping out down below; sometimes they don’t and are lost forever (like my car keys!).

Wrapping dolls in blankets is actually an exension of this idea, as is playing hide-and-seek and making dens. Children learn that they can make themselves disappear, not just objects.

This schema is called enveloping. If your child has ever painted a lovely picture only to cover it completely with a second coat of paint, you’ll know what I’m talking about. Just like peekaboo, she is developing her understanding that the picture continues to exist beneath the concealing second coat.

Understanding children’s drawings is easy if you pay attention

If you look carefully at Figure 1, you’ll see a dark blob. Here it is, magnified:

Can you see that there is a faint circle underneath the colouring in? Within the circle is a cross.

Here are the steps she went through to produce the ‘blob’:

We can see instantly that she was exploring her current graphic schema interests. There was nothing haphazard about this picture. She drew a cross, enclosed it and then enveloped it.

As a parent, if I’d only looked at the finished piece, I’d see nothing more than some sloppy colouring in. She didn’t take care to stay within the lines.

But now we know that this is the most interesting element of the whole piece. And it wasn’t sloppy colouring in – she was trying to cover up the lines beneath.

There’s so much you can do if you can interpret your child’s drawings. It gives you a window into her mind as well as her fine motor skills, and it’s a great jumping off point for learing to write.

One week later…

Let’s jump forward in time by one week. My daughter has continued her exploration of lines, grids, enclosures and enveloping. Has she learnt anything new?

Lines and grids

Now that you know a little more about graphic schemas, you may have realised how futile it is to ask your child to name her pictures – or to make suggestions about what to draw.

Can you draw a railway track? I prompted, knowing that she likes to produce grids.

Yes, here is a train line. And here is another one.

She later added to the picture, but the first version looked like this:

She then enclosed the track in a rectangle.

Daughter: They are in the station.

Me: Can you draw a train to go with it?

I was hoping for a steam train, with a triangular cowcatcher at the front to demonstrate her progress with diagonals.

But, of course, she wasn’t really interested in drawing trains.

Instead, she was enjoying the process of making lines cross at 90º, so she carried on adding more and more railway sleepers, until the track was completely obscured. By the time she had finished, it didn’t look much like a station anymore, but she seemed pleased with her work all the same. Looking at it, she realised it would have to be renamed – because adults always want to you to name your drawings.

It’s a hairy chocolate bar, she said airily, anticipating my question.

At this point, most adults make the mistake of asking the child to colour it in or to add more detail.

They hear ‘chocolate bar’ and insist on colourful packaging and perhaps a logo.

But all she cared about was making another grid.

The picture is perfect as it is. It was a vehicle for her explorations and has served its purpose.

More examples of graphic schemas this week

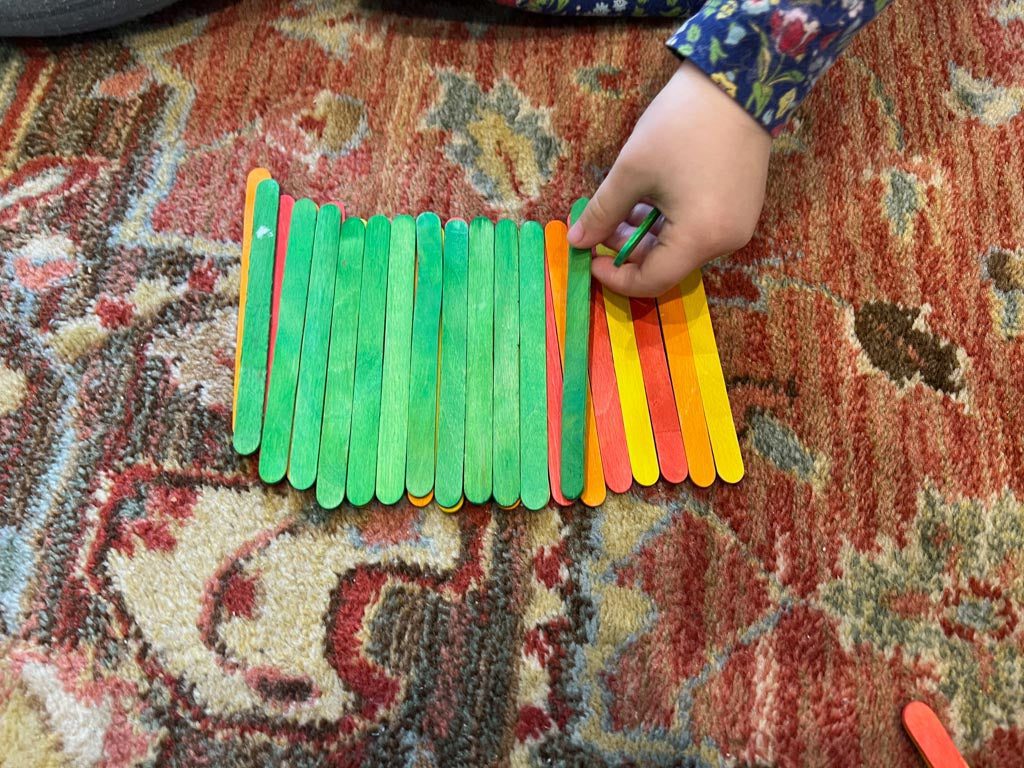

My daughter has a mental model of how lines intersect. I thought I’d continue the railway theme by starting a track of my own using lolly sticks. Perhaps she would continue it herself?

Erm… No.

She preferred to make her own version.

I’d created parallel lines of track but her interest lay in the simple crossing of one line over another. Her sleepers were almost parallel. You can see the beginnings of a grid. But the important thing, from her perspective, was the idea of crossing.

This led to an interest in compasses.

I don’t know what first inspired it. Now that she’s at nursery, she is exposed to all kinds of influences that I’m not aware of, so perhaps it came from there. Anyway, she wanted to make something like this:

I’m sorry about the toothpaste.

This compass came free with Swashbuckle! magazine and my daughter combined her love of intersecting lines with her other true love – enveloping. So she enveloped the toothpaste inside the compass – and then enveloped the compass inside her bag.

To the untrained eye, a it’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma… but you understand schemas, so you see its inevitability. Of course she would try to obscure the lines.

Anyway, the compass pleased her, so she made one with pattern blocks:

Not bad.

And one with lolly sticks. Note the enclosure made from dried pasta.

Again, a good attempt.

Notice, also, the ‘bonfire’ bottom left. My daughter saw the orange and yellow sticks and was inspired to make it. Is it a coincidence that the sticks are arranged across each other, like a compass? I don’t think so.

The trouble with drawing

Do you remember the difficulty she had drawing triangular ears for The Big Bad Wolf? They were curved rather than pointed.

Drawing a compass, which she was motivated to try independently, is even trickier. Here, on her second attempt, she manages a three-pointed star.

Why is it so difficult?

There is the fine motor challenge of controlling the pencil. Draw a line to the perimeter and then come back to the centre, gently broadening the triangle as you go, then make a 90º turn and go back out again. Repeat three more times, with perfect accuracy, and you’ll be back where you started.

This also demands good spatial reasoning as the arrows must line up both vertically and horizontally.

It’s also a test of working memory to remember and execute so many steps.

If I had only given my daughter a pencil and paper, I would have said that the compass shape was too complicated for her to manage. But we can see from her pattern block and lolly stick models that she understands the form a compass takes: She has the spatial reasoning. It’s the fine motor and working memory challenges that trip her up.

The same is true for letter-formation. There are letters she can’t write, but given lolly sticks, circles and semicircles, she has no trouble assembling them.

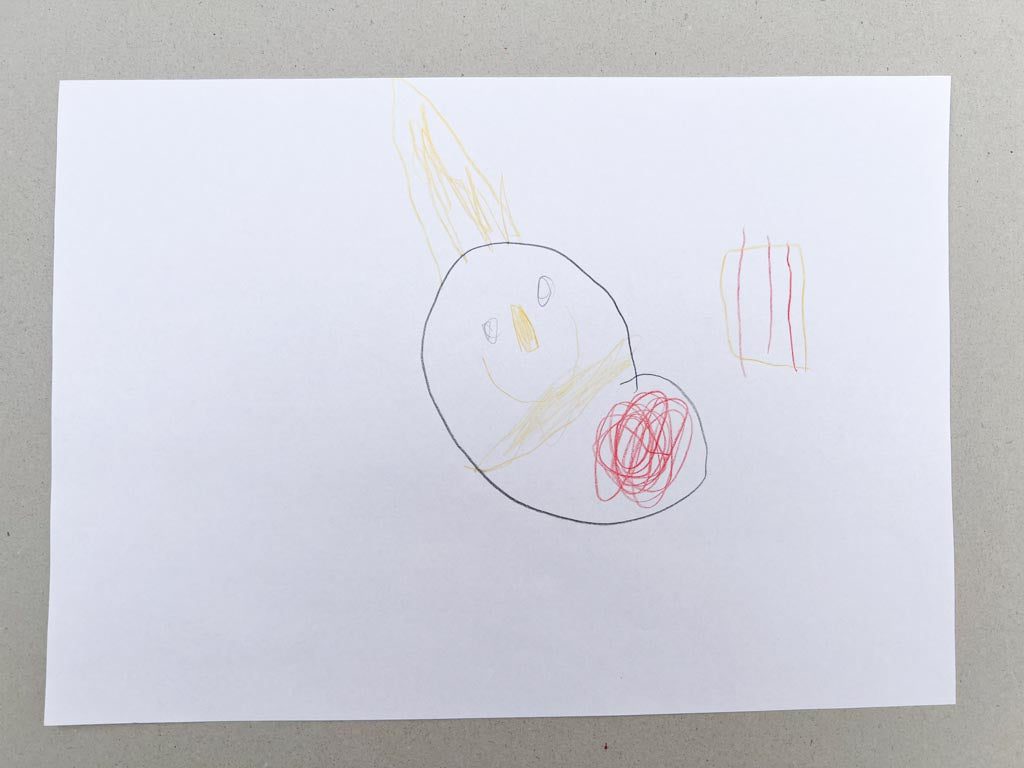

Enclosing and enveloping

Do you remember my daughter’s black splodge from last week? It didn’t look like much but by looking at earlier versions of her work we understood that she was exploring the idea of things being covered up and inside.

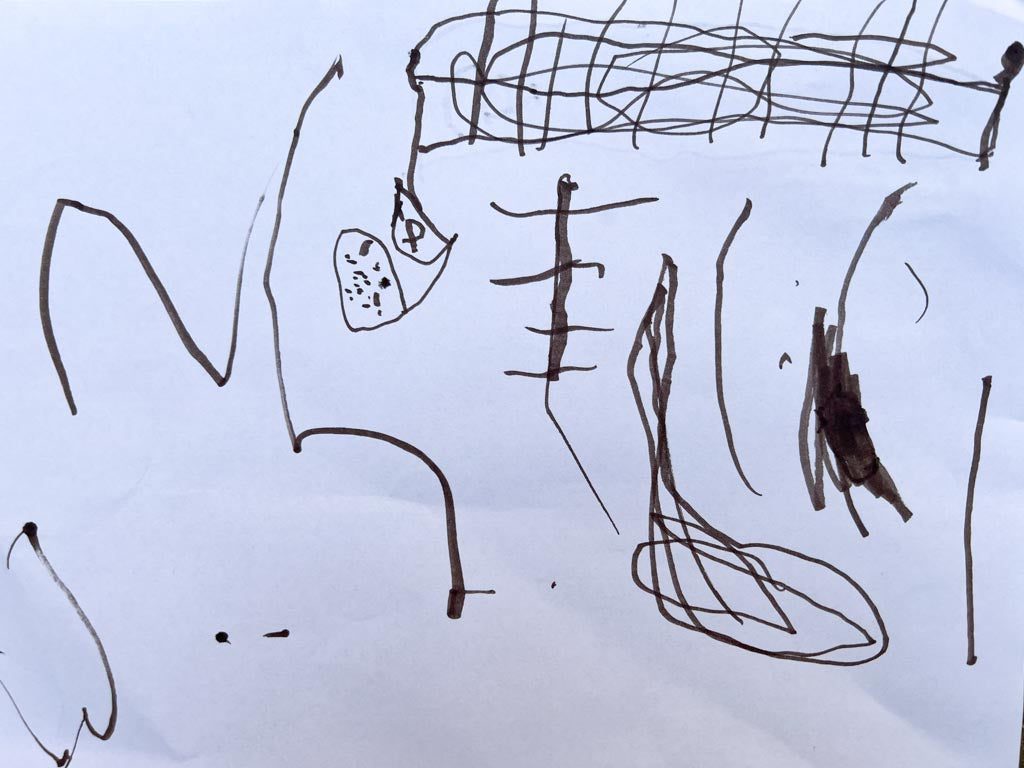

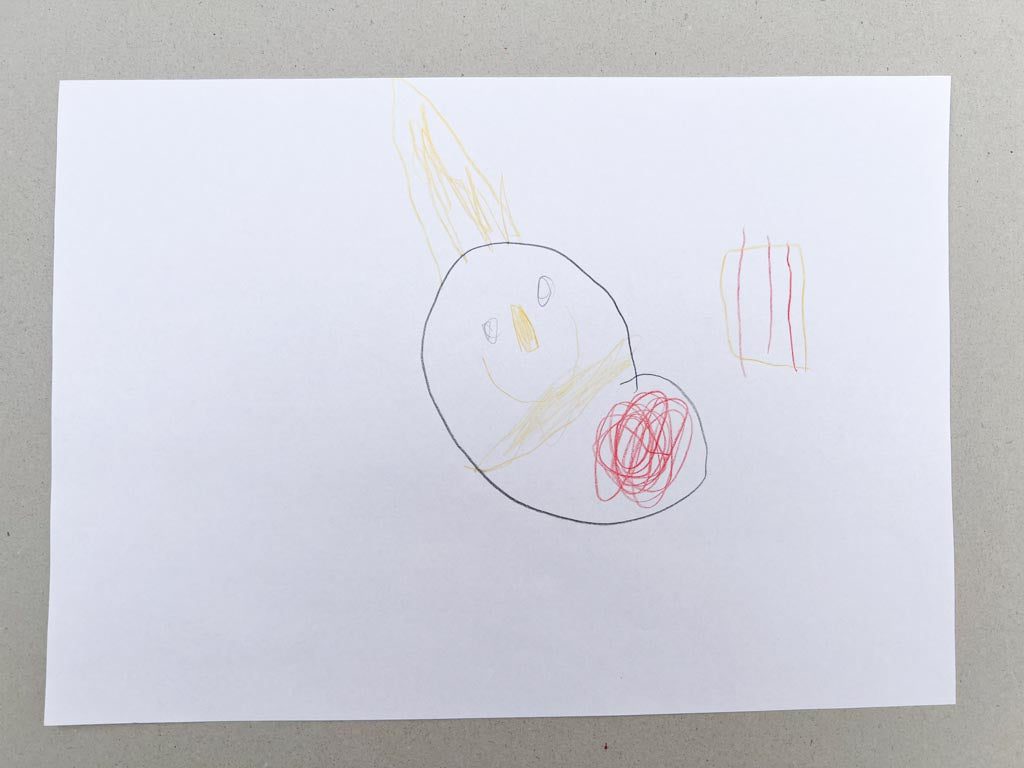

The theme continued this week with a picture of a snowman.

Children interested in enveloping like to dress up. Hats and scarves are a popular choice. Here a snowman wears his winter clothes, and there’s a curious red squiggle in his tummy:

He’s been eating red sausages. He has a triangle carrot nose. This is his hat. He is wearing a scarf.

He’s by the heaters. The lines are red because it’s hottening up.

On the face of it, it’s just another slapdash scribble by a four-year-old. It took 30 seconds to draw. Not her best work, you might think.

But look again. Sausages enveloped in his tummy, scarf and hat enveloping his head, parallel vertical lines enclosed within the heater.

She doesn’t care how it looks. Her only concern is exploring her schemas.

One last picture for you. Again, it’s unremarkable.

I wanted to see if she could draw a Christmas tree as it’s really just three stacked triangles. She couldn’t. So I drew one for her. Once again, my agenda was subverted. She wasn’t interested in tackling a shape that was too difficult. Her interest lay in enclosing and enveloping.

She drew dozens of baubles.

Looking at them, I see lots of circular enclosures, enclosed within the outline of a tree.

Of the squiggle on the trunk, she said, “This is the mud. It’s in the trunk. It can’t get out.”

It looks like sloppy colouring but really she is exploring the idea of enveloping, of the mud being contained within the trunk.

An important lesson

If there’s one message you get from the above is that your child knows best. Give her the time and space to explore and she’ll pose her own questions – and find her own answers.

Also, the materials you offer matter. Next time you’re thinking about buying some new resources, why not give her (age permitting) lolly sticks, matchsticks or pattern blocks? And take the time to observe and reflect. What is she trying to create? Can you take that interest and find other ways to explore it? Perhaps there are grids or parallel lines at the playground? Or, on a trip to the woods, a den to envelop herself in?

Over the past week, have you spotted any patterns in your child’s play? It’s amazing what you notice when you know how to look.

In the last couple of emails, we looked at my daughter’s creations through the lens of graphic schemas. She has continued to work busily on her representations but this time our focus is different. We are learning to observe and to think about next steps. Spotting schemas is fun but it’s not much use if you don’t do anything with the knowledge.

Another week later…

When was the last time you sat down and simply watched your child play? No phone in hand, no television on in the background, just sitting and noticing?

Try it.

You can ask questions if you like but, like Holden Caulfield, children are unreliable narrators.

What are you drawing?

It’s a train track in a station.

Then, two minutes later:

It’s a hairy chocolate bar.

Your child names her pictures just to please you. She knows that adults expect drawings to be about something.

Instead of talking, observe. My daughter narrates as she goes, describing her work. I like to write down her words, but I don’t believe they tell the whole story.

So, here are this week’s pictures. I offer my interpretations. But I could be wrong.

The important thing is that you get into the habit of slowing down and looking.

This exercise isn’t about writing. You could do it with a baby at her treasure basket or a toddler enjoying her first set of blocks. The important thing is to look.

Modelling clay

Here’s my daughter, playing with FIMO. Look at what she carved.

You can see from the purple block that her interest in parallel vertical lines continues.

But what’s going on with the blue square? It looks like a jumble of lines.

The secret doesn’t reveal itself unless you watched her make it.

We know she likes lines and grids so 1 & 2 are no surprise. But look at 3. She has made a discovery: take a square and draw a line from one corner to the opposite one and you have a triangle.

Going back to the part of this mini series, we remember the trouble she had forming three-sided shapes. Her early attempts had flat or curved tops. They were more like a trapezius, a pyramid with the top chopped off.

The Big Bad Wolf’s rounded ears made him look like a bunny rabbit.

But now she has discovered a fail-safe way to create a perfect triangle, without a moment’s instruction from me:

Take a square and divide it diagonally.

Where could this take us next? Origami? Paper aeroplanes? Folding napkins at mealtimes? You can see that all these activities are potentially interesting to her.

After that, making squares from two triangles using attribute blocks.

But does it work for all triangles? I see more learning ahead.

This is where nurseries and kindergartens win.

At home, most of us just have a toy box and a television. No wonder our children get bored.

But free access to blocks, shapes, sticks and paper gives you all the tools you need to explore indefinitely. If you have a good idea, just pull the materials you need off the shelf and get making.

Enveloping, revisited

Enveloping is the idea that you can wrap or cover something but that it continues to exist underneath.

Here’s another self-chosen activity from this week.

It’s a fire in a barbecue. These are peas in a pod. I am putting them on top.

Interesting…

The peas are (imagined to be) enveloped in their pod. The fire is in the process of being enveloped by the peas (she would eventually entirely cover the red and orange sticks with green).

Last week it was a snowman wearing a hat and scarf with red sausages in his tummy. This week it’s peas. But because we have been paying attention, we know that the schema is the same. Comparing the two pictures it’s almost unbelievable that they are related.

But they are.

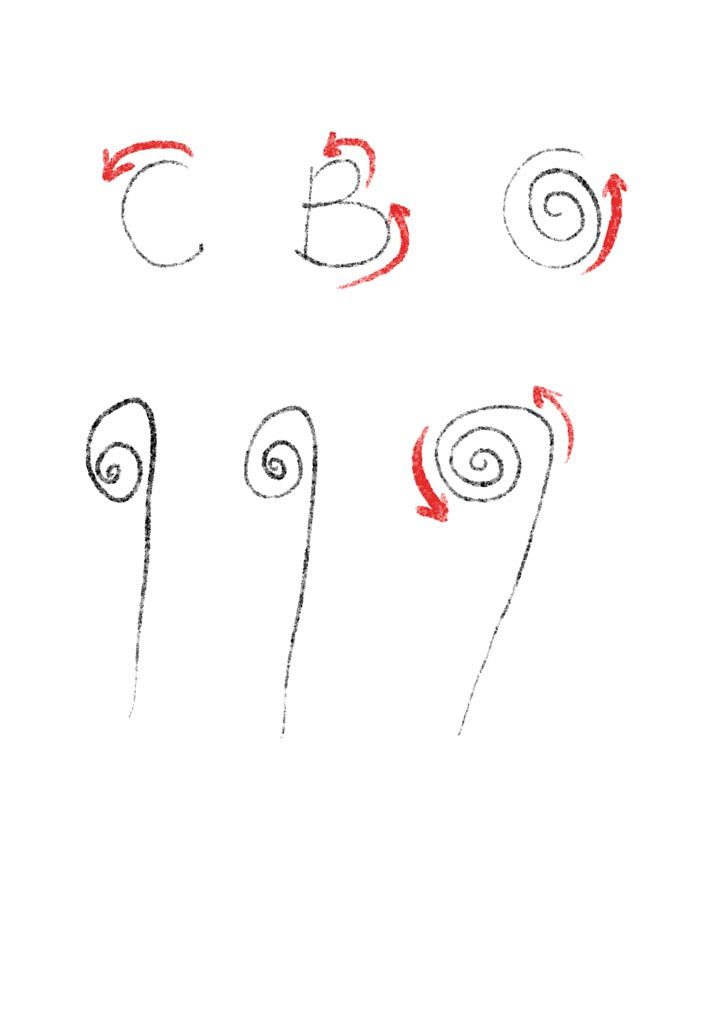

Circles, spirals and rotation

Playdough is our everyday modelling material in the 100 Toys house, but we also like plasticine and clay. This week we got out the FIMO because it’s great for fine detail and the creations are more permanent. My daughter immediately saw the possibilities.

She rolled out long strips. It seemed natural to curl them round. Soon she had wound a tight spiral.

And then she did something interesting.

She enclosed it.

It’s wrapped up in green. It’s a watermelon.

A watermelon’s flesh is enveloped. It’s hidden inside until you cut it open.

Later that day, she sat down to draw.

‘C’ is for her name. ‘C’ is half an anti-clockwise turn. She drew three and enclosed them.

Then she noticed that she could start the anti-clockwise turn from a vertical line to make an enclosure and stack another one on top to make a capital ‘B’.

From there it was a quick step to a spiral and then a spiral at the end of a long line, like an unfolding fern.

It’s a flat trumpet at a party!

The new shape reminded her of something:

It’s a flat trumpet at a party!

That’s a party blower to you and me.

Party blowers 4 – 7 are drawn with confidence. But look at the three on the left:

An upside down one, Daddy!

Upside down seems harder to draw. The spiral starts at the top and continues all the way down, instead of beginning with a straight line.

Schemas represent our best thinking about a shape or action. But there’s always room for improvement. Spiral at the top? Easy. Spiral at the bottom? Could do better.

By the time she reaches her third upside-down spiral, we notice an improvement. The line is almost straight. Schemas build on prior knowledge. They save us from reinventing the wheel every time. My daughter could draw lines and spirals. The new skill was to connect them.

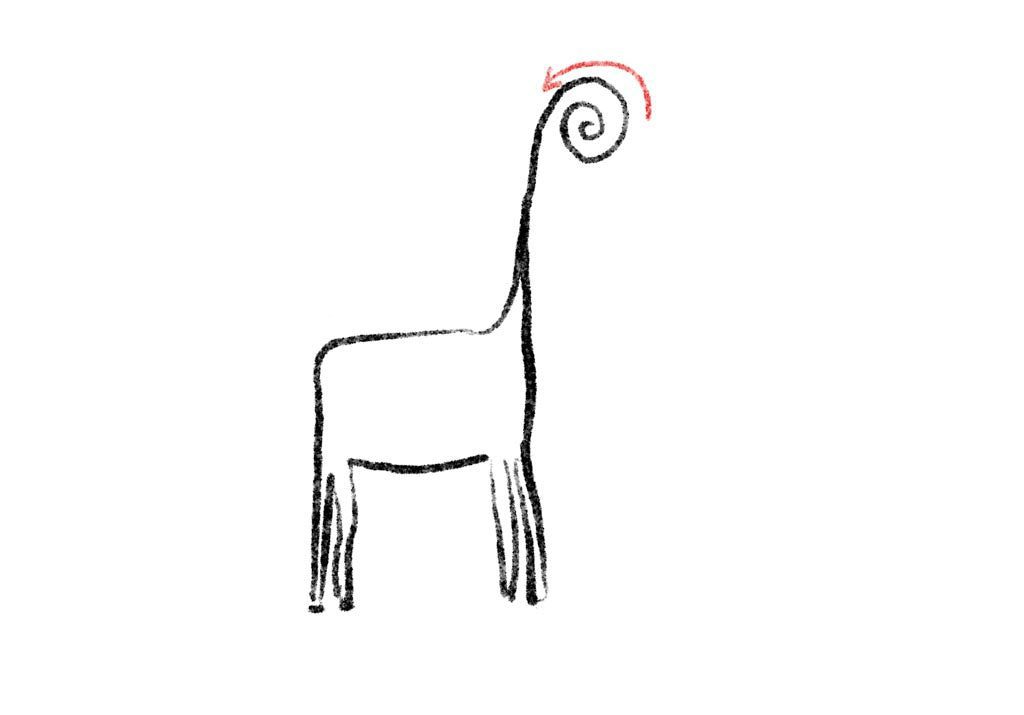

Slides and spirals at the zoo

Can we go to the zoo? I want to see the elephants because they are like a slide.

Hmm… Why is she interested in the elephant’s trunk?

And I want to see the giraffes because they have a long neck

Do you think she was thinking about something in particular when she chose this animal? Me too.

Giraffes and elephants have something in common: a long body part that curves at the end.

If we went to the zoo, my guess is that she would like to see goats with spiral horns, snakes coiled around a branch and monkeys with curly tails.

Closer to home, we could look at windmills, pinwheels, fidget spinners, spinning tops, streamers, party blowers, Catherine wheels and snails.

As I wrote this, completely out of the blue she asked me for a pull-back car. She has never shown any interest in vehicles before. Could it be because this type uses a (spiral) coiled spring to move? Or is she interested in the rotating wheels? There’s only one way to find out.

Something else she was interested in this week was pirouettes. You’ve probably already worked out where I’m going with this: rotation schema. Round and round, but using her body, not a pencil.

An interest in circles and enclosing has progressed to a fascination with twisting and spirals.

‘Letter music’

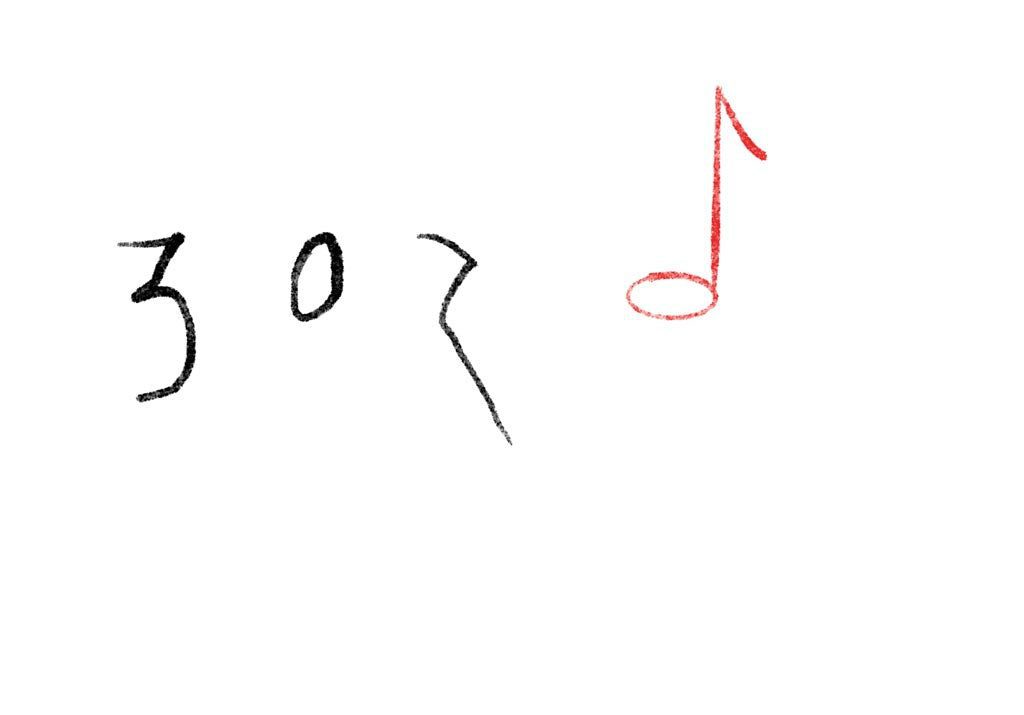

Another afternoon, another indecipherable picture.

It’s a trumpet with letter music coming out.

‘Letter music’ was a word she spontaneously invented to describe musical notation.

She knew she couldn’t draw sound so she used symbols instead.

Her older siblings are learning to read music. She has made the association between the symbol (in this case a quaver) and the sound that comes out of the trumpet. What she was trying to draw, was this:

The first three symbols were her attempt at the fourth. Without a quaver to copy, she had to rely on her memory. It has a circle, a stick and a squiggly line. She got the elements right, she simply couldn’t arrange them in order, spatially.

In the end, she gave up, and decided that vertical lines coming out of the trumpet would suffice to represent the sound.

The ‘trumpet’, I think, was inspired by all the brass and woodwind instruments she knows. A mix of clarinet, trumpet and saxophone. Her instrument should curve round at the top, she decided. Again, her schema for trumpets was incomplete. What kind of shape should it be? She was unsure, so she drew it, hoping that it would look right. It didn’t, so she continued the line to make a spiral. Still unconvinced, she moved on to the ‘letter music’.

This kind of problem applies to us too. I bet if you tried to draw a bicycle, you’d get it wrong first time. We all know what a bicycle looks like but most of us haven’t paid enough attention to remember exactly what angle the seat post and top post meet at and where the forks attach. It’s only when we try to draw a bike that the gaps in our knowledge are exposed.

Final word

Do you see how your child has a natural urge to explore all the concepts that she needs to learn?

She is able to hypothesise and test. She understands the gaps in her knowledge and systematically works to fill them.

All you have to do is pay attention.

Notice what she needs, and offer the right environment and materials for her to make her own discoveries.

Read more about starting school.

Have you run out of ideas?

What if you didn’t have to trawl the internet for play inspiration? What if your child’s freely-chosen activities were simple to set up, educational and deeply engaging?

How would that change things?

Our courses, A Year With My Child, Get Set Five and 5 Plus are designed for parents of toddlers, preschoolers and the over 5s and they’re packed full of fun and sensible advice.

Enter your email and we’ll send you free modules from each course. And then sit back and relax as your child learns to make her own fun.

The 100 Toys Method

Simplify

Our introductory guide will help you declutter and get back to basics

Learn

Understand how children learn and the key changes they go through.

Play

Introduce open-ended activities that encourage independent play.